The process of score study, interpretation, and internalization of a work of art is a life long journey for all of us as music educators. These skills are paramount for rigorously selecting repertoire for ourselves and our students, as well as plumbing the depths of each work in search of the “implied meaning in the written symbol” (Eugene Corporon). This journey between conductor and their score has often been described as building a life long friendship, and has been been brilliantly portrayed by conductor Allan McMurray in a YouTube video entitled “The Score is your Friend (if you have never seen this, please check it out!).

Ironically, prior to the end of the 20th century, there were very few resources that took this process of score study and codified it for young conductors. While there are some excellent books on the subject of conducting by Herman Scherchen, Gunther Schuller, Diane Wittry, and Leonard Slatkin (just to name a few), there was a noticeable absence of a pedagogical method of score study that students and professionals could consult and absorb into their learning process. This all changed in 1990 with the publication of Guide to Score Study by Frank Battisti and Robert Garafalo. I was very fortunate to come into contact with this text in my senior year of college soon after it was released, and it has been a source of constant inspiration and information during my journey as a conductor and educator.

Both authors bring a wealth of experience to the creation of this text. Dr. Garofalo is Emeritus Professor/Conductor of Bands at The Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, and a fellow Pennsylvanian! Professor Frank Battisti is Director of Bands Emeritus and Founder of the Wind Ensemble at the New England Conservatory of Music, as well as leading one of the top band programs at Ithaca High School (NY). Both of these gentlemen have numerous individual publications to their credit, many of which have become standards in the industry. Although this book is not the subject of this review, I would highly recommend a series of books that have been recently written by Mr. Battisti, including The Winds of Change, On Becoming a Conductor, and The Best We Can Be.

This text is divided into four major sections that detail the process of score study and preparation: Score Orientation, Score Reading, Score Analysis, and Score Study. Several appendices at the end of the book provide a treasure trove of information about transposition and clefs, practice materials for score study and score orientation, methods for marking a score, materials relating to Percy Grainger’s Irish Tune from County Derry (the primary score that is discussed in each chapter), and a lengthy bibliography that would satiate the most curious conductor/teachers.

After twenty-three years as an educator, I still get a feeling of excitement of receiving a new score in the mail, and the accompanying nervousness that I won’t be able to absorb all of the information that I see in front of me. When we consider all the information to be absorbed from the printed notation, the prerequisite knowledge that we need about the composer and the background of the piece (not to mention the pedagogical knowledge about each instrument), and then trying to use our own musical imagination to interpret this framework, it can easily become overwhelming. This book serves to create a clear pathway to digesting the most complex of scores, and provides clear and concrete outcomes for each step in the process.

As mentioned above, the authors use Percy Grainger’s Irish Tune from County Derry as the work that is taken through each step in the score study process. Part one of the score study process, Score Orientation, requires the conductor to “acquire an overview of the entire work” through an examination of the mechanics of the score (transposed vs. C score, clefs, musical terms, etc.) as well gleaning information from the title page and introductory pages found within. I have found that the more experience I have gained as a music educator, the more beneficial this process has become to me as a conductor. As an example, when I see a new work by Frank Ticheli, I have conducted enough of his music that it sets an aural expectation for what I am about to find flipping through the score. Titles such as “symphony”, “suite”, and “divertimento”, are incredibly helpful in anticipating the architecture and design of a new score as well.

Step two, Score Readings, requires the conductor to “achieve an overall sound image of the music in the mind and to develop an intuitive musical feeling for the expressive potential of the music.” This step includes reading the score at a slow, consistent tempo developing an overall “musical imagination, feelings, and intuition” of the work.

The authors strongly suggest that the conductor not use a recording to study the work at this point, or at most points in the process. While I do understand and respect their reasoning, I do think that a recording can be useful provided that it is used early in the process, and that the recording is put away after one has absorbed the overall gestalt of the work. Also, if multiple recordings are available, that can be extraordinarily useful in assessing the quality of a given composition. The trap that we want to avoid is using a recording as our score study process, and given that spare time is the most precious commodity in a music teacher’s life, we are always looking at ways to make our work more efficient. While this is a minor disagreement with the authors, the digital resources that we have now far outweigh what was previously available in 1990. While I cannot speak for the authors, I do wonder if they would revise their opinion on this subject given the technology that we have now.

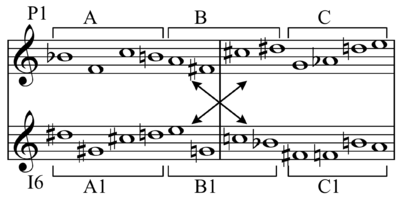

Step three, Score Analysis, is the most detailed part of the process where the conductor analyzes all of the requisite musical dimensions of the work (melody, harmony, form, rhythm, orchestration, dynamics, articulations, expressive terms, etc.). This chapter some of the most detailed analysis of Irish Tune that I have encountered in my 23 years of teaching, including a complete harmonic analysis, phrasal analysis, and flowcharts for orchestration, rhythm, and overall design.

It is important to note here that while all of these methods and resources are incredibly helpful in assimilating a particular work, the conductor should not feel bound to use all of them when learning a score. For example, many works do not lend themselves well to traditional Roman numeral harmonic analysis, but they could benefit from a detailed rhythmic analysis (the last portion of the Rite of Spring as an example). It has been helpful for me to use this chapter as a tool box, making use of individual analyses depending on the demands of the score.

Step four, Score Interpretation assists the conductor in making creative decisions based upon all of the music “building blocks” of the score. To illustrate this, the authors annotate a full score to Irish Tune with interpretive decisions based upon the information gleaned in the previous three chapters.

In conclusion, this text belongs on the bookshelf of every instrumental conductor. For those new to the art and craft of studying a score, it will provide immense guidance towards developing this important skill. For those of us who are seasoned conductor/teachers, it provides continuous inspiration and ideas towards discovering the music between the notes. I recommend it strongly to you!